- November 30, 2022

- Posted by: admin

- Category: BitCoin, Blockchain, Cryptocurrency, Investments

The IMF and World Bank do not seek to fix poverty, but only to enrich creditor nations. Could Bitcoin create a better global economic system for the developing world?

This is an opinion editorial by Alex Gladstein, chief strategy officer of the Human Rights Foundation and author of “Check Your Financial Privilege.”

I. The Shrimp Fields

“Everything is gone.”

–Kolyani Mondal

Fifty-two years ago, Cyclone Bhola killed an estimated 1 million people in coastal Bangladesh. It is, to this day, the deadliest tropical cyclone in recorded history. Local and international authorities knew well the catastrophic risks of such storms: in the 1960s, regional officials had built a massive array of dikes to protect the coastline and open up more territory for farming. But in the 1980s after the assassination of independence leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, foreign influence pushed a new autocratic Bangladeshi regime to change course. Concern for human life was dismissed and the public’s protection against storms was weakened, all in order to boost exports to repay debt.

Instead of reinforcing the local mangrove forests which naturally protected the one-third of the population that lived near the coast, and instead of investing in growing food to feed the quickly growing nation, the government took out loans from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in order to expand shrimp farming. The aquaculture process — controlled by a network of wealthy elites linked to the regime — involved pushing farmers to take out loans to “upgrade” their operations by drilling holes in the dikes that protected their land from the ocean, filling their once-fertile fields with saltwater. Then, they would work back-breaking hours to hand-harvest young shrimp from the ocean, drag them back to their stagnant ponds, and sell the mature ones to the local shrimp lords.

With financing from the World Bank and IMF, countless farms and their surrounding wetlands and mangrove forests were engineered into shrimp ponds known as ghers. The area’s Ganges river delta is an incredibly fertile place, home to the Sundarbans, the world’s biggest stretch of mangrove forest. But as a result of commercial shrimp farming becoming the region’s main economic activity, 45% of the mangroves have been cut away, leaving millions of people exposed to the 10-meter waves that can crash against the coast during major cyclones. Arable land and river life has been slowly destroyed by excess salinity leaking in from the sea. Entire forests have vanished as shrimp farming has killed much of the area’s vegetation, “rendering this once bountiful land into a watery desert,” according to Coastal Development Partnership.

The shrimp lords, however, have made a fortune, and shrimp (known as “white gold”) has become the country’s second-largest export. As of 2014, more than 1.2 million Bangladeshis worked in the shrimp industry, with 4.8 million people indirectly dependent on it, roughly half of the coastal poor. The shrimp collectors, who have the toughest job, make up 50% of the labor force but only see 6% of the profit. Thirty percent of them are girls and boys engaged in child labor, who work as much as nine hours a day in the salt water, for less than $1 per day, with many giving up school and remaining illiterate to do so. Protests against the expansion of shrimp farming have happened, only to be put down violently. In one prominent case, a march was attacked with explosives from shrimp lords and their thugs, and a woman named Kuranamoyee Sardar was decapitated.

In a 2007 research paper, 102 Bangladeshi shrimp farms were surveyed, revealing that, out of a cost of production of $1,084 per hectare, the net income was $689. The nation’s export-driven profits came at the expense of the shrimp laborers, whose wages were deflated and whose environment was destroyed.

In a report by the Environmental Justice Foundation, a coastal farmer named Kolyani Mondal said that she “used to farm rice and keep livestock and poultry,” but after shrimp harvesting was imposed, “her cattle and goats developed diarrhea-type disease and together with her hens and ducks, all died.”

Now her fields are flooded with salt water, and what remains is barely productive: years ago her family could generate “18-19 mon of rice per hectare,” but now they can only generate one. She remembers shrimp farming in her area beginning in the 1980s, when villagers were promised more income as well as lots of food and crops, but now “everything is gone.” The shrimp farmers who use her land promised to pay her $140 per year, but she says the best she gets are “occasional installments of $8 here or there.” In the past, she says, “the family got most of the things they needed from the land, but now there are no alternatives but going to the market to buy food.”

In Bangladesh, billions of dollars of World Bank and IMF “structural adjustment” loans — named for the way they force borrowing nations to modify their economies to favor exports at the expense of consumption — grew national shrimp profits from $2.9 million in 1973 to $90 million in 1986 to $590 million in 2012. As in most cases with developing countries, the revenue was used to service foreign debt, develop military assets, and line the pockets of government officials. As for the shrimp serfs, they have been impoverished: less free, more dependent and less able to feed themselves than before. To make matters worse, studies show that “villages shielded from the storm surge by mangrove forests experience significantly fewer deaths” than villages which had their protections removed or damaged.

Under public pressure in 2013 the World Bank loaned Bangladesh $400 million to try and reverse the ecological damage. In other words, the World Bank will be paid a fee in the form of interest to try and fix the problem it created in the first place. Meanwhile, the World Bank has loaned billions to countries everywhere from Ecuador to Morocco to India to replace traditional farming with shrimp production.

The World Bank claims that Bangladesh is “a remarkable story of poverty reduction and development.” On paper, victory is declared: countries like Bangladesh tend to show economic growth over time as their exports rise to meet their imports. But exports earnings flow mostly to the ruling elite and international creditors. After 10 structural adjustments, Bangladesh’s debt pile has grown exponentially from $145 million in 1972 to an all-time high of $95.9 billion in 2022. The country is currently facing yet another balance of payments crisis, and just this month agreed to take its 11th loan from the IMF, this time a $4.5 billion bailout, in exchange for more adjustment. The Bank and the Fund claim to want to help poor countries, but the clear outcome after more than 50 years of their policies is that nations like Bangladesh are more dependent and indebted than ever before.

During the 1990s in the wake of the Third World Debt Crisis, there was a swell of global public scrutiny on the Bank and Fund: critical studies, street protests, and a widespread, bipartisan belief (even in the halls of the U.S. Congress) that these institutions ranged from wasteful to destructive. But this sentiment and focus has largely faded. Today, the Bank and the Fund manage to keep a low profile in the press. When they do come up, they tend to be written off as increasingly irrelevant, accepted as problematic yet necessary, or even welcomed as helpful.

The reality is that these organizations have impoverished and endangered millions of people; enriched dictators and kleptocrats; and cast human rights aside to generate a multi-trillion-dollar flow of food, natural resources and cheap labor from poor countries to rich ones. Their behavior in countries like Bangladesh is no mistake or exception: it is their preferred way of doing business.

II. Inside The World Bank And IMF

“Let us remember that the main purpose of aid is not to help other nations but to help ourselves.”

The IMF is the world’s international lender of last resort, and the World Bank is the world’s largest development bank. Their work is carried out on behalf of their major creditors, which historically have been the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Japan.

The sister organizations — physically joined together at their headquarters in Washington, DC — were created at the Bretton Woods Conference in New Hampshire in 1944 as two pillars of the new U.S.-led global monetary order. Per tradition, the World Bank is headed by an American, and the IMF by a European.

Their initial purpose was to help rebuild war-torn Europe and Japan, with the Bank to focus on specific loans for development projects, and the Fund to address balance-of-payment issues via “bailouts” to keep trade flowing even if countries couldn’t afford more imports.

Nations are required to join the IMF in order to get access to the “perks” of the World Bank. Today, there are 190 member states: each one deposited a mix of their own currency plus “harder currency” (typically dollars, European currencies or gold) when they joined, creating a pool of reserves.

When members encounter chronic balance-of-payments issues, and cannot make loan repayments, the Fund offers them credit from the pool at varying multiples of what they initially deposited, on increasingly expensive terms.

The Fund is technically a supranational central bank, as since 1969 it has minted its own currency: the special drawing rights (SDR), whose value is based on a basket of the world’s top currencies. Today, the SDR is backed by 45% dollars, 29% euros, 12% yuan, 7% yen and 7% pounds. The total lending capacity of the IMF today stands at $1 trillion.

Between 1960 and 2008, the Fund largely focused on assisting developing countries with short-term, high-interest-rate loans. Because the currencies issued by developing countries are not freely convertible, they usually cannot be redeemed for goods or services abroad. Developing states must instead earn hard currency through exports. Unlike the U.S., which can simply issue the global reserve currency, countries like Sri Lanka and Mozambique often run out of money. At that point, most governments — especially authoritarian ones — prefer the quick fix of borrowing against their country’s future from the Fund.

As for the Bank, it states that its job is to provide credit to developing countries to “reduce poverty, increase shared prosperity, and promote sustainable development.” The Bank itself is split up into five parts, ranging from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which focuses on more traditional “hard” loans to the larger developing countries (think Brazil or India) to the International Development Association (IDA), which focuses on “soft” interest-free loans with long grace periods for the poorest countries. The IBRD makes money in part through the Cantillon effect: by borrowing on favorable terms from its creditors and private market participants who have more direct access to cheaper capital and then loaning out those funds at higher terms to poor countries who lack that access.

World Bank loans traditionally are project- or sector-specific, and have focused on facilitating the raw export of commodities (for example: financing the roads, tunnels, dams, and ports needed to get minerals out of the ground and into international markets) and on transforming traditional consumption agriculture into industrial agriculture or aquaculture so that countries could export more food and goods to the West.

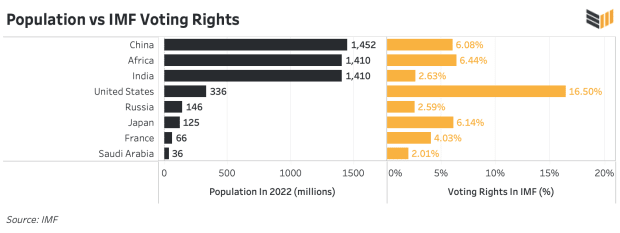

Bank and Fund member states do not have voting power based on their population. Rather, influence was crafted seven decades ago to favor the U.S., Europe and Japan over the rest of the world. That dominance has only weakened mildly in recent years.

Today the U.S. still owns far and away the largest vote share, at 15.6% of the Bank and 16.5% of the Fund, enough to single-handedly veto any major decision, which requires 85% of votes at either institution. Japan owns 7.35% of the votes at the Bank and 6.14% at the Fund; Germany 4.21% and 5.31%; France and the U.K. 3.87% and 4.03% each; and Italy 2.49% and 3.02%.

By contrast, India with its 1.4 billion people only has 3.04% of the Bank’s vote and just 2.63% at the Fund: less power than its former colonial master despite having a population 20 times bigger. China’s 1.4 billion people get 5.7% at the Bank and 6.08% at the fund, roughly the same share as the Netherlands plus Canada and Australia. Brazil and Nigeria, the largest countries in Latin America and Africa, have about the same amount of sway as Italy, a former imperial power in full decline.

Tiny Switzerland with just 8.6 million people has 1.47% of votes at the World Bank, and 1.17% of votes at the IMF: roughly the same share as Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia combined, despite having 90 times fewer people.

These voting shares are supposed to approximate each country’s share of the world economy, but their imperial-era structure helps color how decisions are made. Sixty-five years after decolonization, the industrial powers led by the U.S. continue to have more or less total control over global trade and lending, while the poorest countries have in effect no voice at all.

The G-5 (the U.S., Japan, Germany, the U.K. and France) dominate the IMF executive board, even though they make up a relatively small percent of the world’s population. The G-10 plus Ireland, Australia, and Korea make up more than 50% of the votes, meaning that with a little pressure on its allies, the U.S. can make determinations even on specific loan decisions, which require a majority.

To complement the IMF’s trillion-dollar lending power, the World Bank group claims more than $350 billion in outstanding loans across more than 150 countries. This credit has spiked over the past two years, as the sister organizations have lent hundreds of billions of dollars to governments who locked down their economies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over the past few months, the Bank and Fund began orchestrating billion-dollar deals to “save” governments endangered by the U.S. Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes. These clients are often human rights violators who borrow without permission from their citizens, who will ultimately be the ones responsible for paying back principal plus interest on the loans. The IMF is currently bailing out Egyptian dictator Abdel Fattah El-Sisi — responsible for the largest massacre of protestors since Tiananmen Square — for example, with $3 billion. Meanwhile, the World Bank was, during the past year, disbursing a $300 million loan to an Ethiopian government that was committing genocide in Tigray.

The cumulative effect of Bank and Fund policies is much larger than the paper amount of their loans, as their lending drives bilateral assistance. It is estimated that “every dollar provided to the Third World by the IMF unlocks a further four to seven dollars of new loans and refinancing from commercial banks and rich-country governments.” Similarly, if the Bank and Fund refuse to lend to a particular country, the rest of the world typically follows suit.

It is hard to overstate the vast impact the Bank and Fund have had across developing nations, especially in their formative decades after World War II. By 1990 and the end of the Cold War, the IMF had extended credit to 41 countries in Africa, 28 countries in Latin America, 20 countries in Asia, eight countries in the Middle East and five countries in Europe, affecting 3 billion people, or what was then two-thirds of the global population. The World Bank has extended loans to more than 160 countries. They remain the most important international financial institutions on the planet.

III. Structural Adjustment

“Adjustment is an ever new and never-ending task”

–Otmar Emminger, former IMF director and creator of SDR

Today, financial headlines are filled with stories about IMF visits to countries like Sri Lanka and Ghana. The outcome is that the Fund loans billions of dollars to countries in crisis in exchange for what is known as structural adjustment.

In a structural-adjustment loan, borrowers not only have to pay back principal plus interest: they also have to agree to change their economies according to Bank and Fund demands. These requirements almost always stipulate that clients maximize exports at the expense of domestic consumption.

During research for this essay, the author learned much from the work of the development scholar Cheryl Payer, who wrote landmark books and papers on the influence of the Bank and Fund in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. This author may disagree with Payer’s “solutions” — which, like those of most critics of the Bank and Fund, tend to be socialist — but many observations she makes about the global economy hold true regardless of ideology.

“It is an explicit and basic aim of IMF programs,” she wrote, “to discourage local consumption in order to free resources for export.”

This point cannot be stressed enough.

The official narrative is that the Bank and Fund were designed to “foster sustainable economic growth, promote higher standards of living, and reduce poverty.” But the roads and dams the Bank builds are not designed to help improve transport and electricity for locals, but rather to make it easy for multinational corporations to extract wealth. And the bailouts the IMF provides aren’t to “save” a country from bankruptcy — which would probably be the best thing for it in many cases — but rather to allow it to pay its debt with even more debt, so that the original loan doesn’t turn into a hole on a Western bank’s balance sheet.

In her books on the Bank and Fund, Payer describes how the institutions claim that their loan conditionality enables borrowing countries “to achieve a healthier balance of trade and payments.” But the real purpose, she says, is “to bribe the governments to prevent them from making the economic changes which would make them more independent and self-supporting.” When countries pay back their structural adjustment loans, debt service is prioritized, and domestic spending is to be “adjusted” downwards.

IMF loans were often allocated through a mechanism called the “stand-by agreement,” a line of credit that released funds only as the borrowing government claimed to achieve certain objectives. From Jakarta to Lagos to Buenos Aires, IMF staff would fly in (always first or business class) to meet undemocratic rulers and offer them millions or billions of dollars in exchange for following their economic playbook.

Typical IMF demands would include:

- Currency devaluation

- Abolition or reduction of foreign exchange and import controls

- Shrinking of domestic bank credit

- Higher interest rates

- Increased taxes

- An end to consumer subsidies on food and energy

- Wage ceilings

- Restrictions on government spending, especially in healthcare and education

- Favorable legal conditions and incentives for multinational corporations

- Selling off state enterprises and claims on natural resources at fire sale prices

The World Bank had its own playbook, too. Payer gives examples:

- The opening up of previously remote regions through transportation and telecommunications investments

- Aiding multinational corporations in the mining sector

- Insisting on production for export

- Pressuring borrowers to improve legal privileges for the tax liabilities of foreign investment

- Opposing minimum wage laws and trade union activity

- Ending protections for locally-owned businesses

- Financing projects that appropriate land, water and forests from poor people and hand them to multinational corporations

- Shrinking manufacturing and food production at the expense of the export of natural resources and raw goods

Third World governments have historically been forced to agree to a mix of these policies — sometimes known as the “Washington Consensus” — in order to trigger the ongoing release of Bank and Fund loans.

The former colonial powers tend to focus their “development” lending on former colonies or areas of influence: France in West Africa, Japan in Indonesia, Britain in East Africa and South Asia and the U.S. in Latin America. A notable example is the CFA zone, where 180 million people in 15 African countries are still forced to use a French colonial currency. At the suggestion of the IMF, in 1994 France devalued the CFA by 50%, devastating the savings and purchasing power of tens of millions of people living in countries ranging from Senegal to Ivory Coast to Gabon, all to make raw goods exports more competitive.

The outcome of Bank and Fund policies on the Third World has been remarkably similar to what was experienced under traditional imperialism: wage deflation, a loss of autonomy and agricultural dependency. The big difference is that in the new system, the sword and the gun have been replaced by weaponized debt.

Over the last 30 years, structural adjustment has intensified with regard to the average number of conditions in loans extended by the Bank and Fund. Before 1980, the Bank did not generally make structural adjustment loans, most everything was project- or sector-specific. But since then, “spend this however you want” bailout loans with economic quid pro quos have become a growing part of Bank policy. For the IMF, they are its lifeblood.

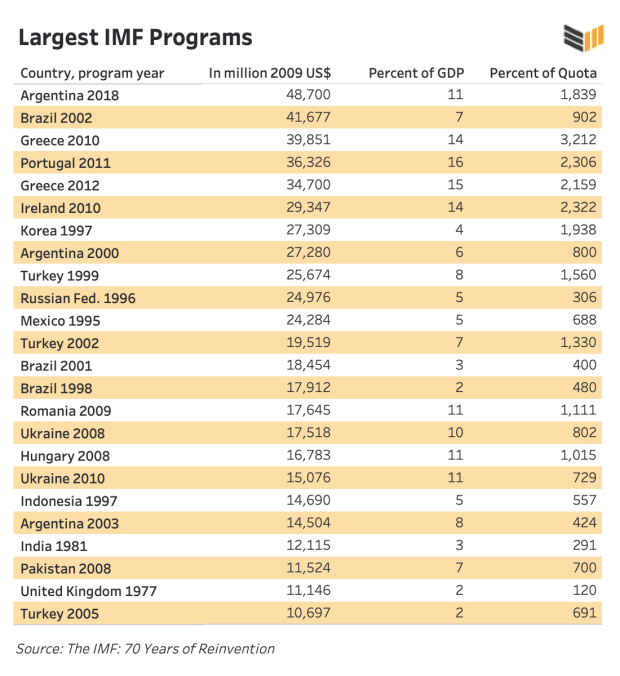

For example, when the IMF bailed out South Korea and Indonesia with $57 billion and $43 billion packages during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, it imposed heavy conditionality. Borrowers had to sign agreements that “looked more like Christmas trees than contracts, with anywhere from 50 to 80 detailed conditions covering everything from the deregulation of garlic monopolies to taxes on cattle feed and new environmental laws,” according to political scientist Mark S. Copelvitch.

A 2014 analysis showed that the IMF had attached, on average, 20 conditions to each loan it gave out in the previous two years, a historic increase. Countries like Jamaica, Greece and Cyprus have borrowed in recent years with an average of 35 conditions each. It is worth noting that Bank and Fund conditions have never included protections on free speech or human rights, or restrictions on military spending or police violence.

An added twist of Bank and Fund policy is what is known as the “double loan”: money is lent to build, for example, a hydroelectric dam, but most if not all of the money gets paid to Western companies. So, the Third World taxpayer is saddled with principal and interest, and the North gets paid back double.

The context for the double loan is that dominant states extend credit through the Bank and Fund to former colonies, where local rulers often spend the new cash directly back to multinational companies who profit from advising, construction or import services. The ensuing and required currency devaluation, wage controls and bank credit tightening imposed by Bank and Fund structural adjustment disadvantage local entrepreneurs who are stuck in a collapsing and isolated fiat system, and benefit multinationals who are dollar, euro or yen native.

Another key source for this author has been the masterful book “The Lords of Poverty” by historian Graham Hancock, written to reflect on the first five decades of Bank and Fund policy and foreign assistance in general.

“The World Bank,” Hancock writes, “is the first to admit that out of every $10 that it receives, around $7 are in fact spent on goods and services from the rich industrialized countries.”

In the 1980s, when Bank funding was expanding rapidly around the world, he noted that “for every US tax dollar contributed, 82 cents are immediately returned to American businesses in the form of purchase orders.” This dynamic applies not just to loans but also to aid. For example, when the U.S. or Germany sends a rescue plane to a country in crisis, the cost of transport, food, medicine and staff salaries are added to what is known as ODA, or “official development assistance.” On the books, it looks like aid and assistance. But most of the money is paid right back to Western companies and not invested locally.

Reflecting on the Third World Debt Crisis of the 1980s, Hancock noted that “70 cents out of every dollar of American assistance never actually left the United States.” The U.K., for its part, spent a whopping 80% of its aid during that time directly on British goods and services.

“One year,” Hancock writes, “British tax-payers provided multilateral aid agencies with 495 million pounds; in the same year, however, British firms received contracts worth 616 million pounds.” Hancock said that multilateral agencies could be “relied upon to purchase British goods and services with a value equivalent to 120% of Britain’s total multilateral contribution.”

One starts to see how the “aid and assistance” we tend to think of as charitable is really quite the opposite.

And as Hancock points out, foreign-aid budgets always increase no matter the outcome. Just as progress is evidence that the aid is working, a “lack of progress is evidence that the dosage has been insufficient and must be increased.”

Some development advocates, he writes, “argue that it would be inexpedient to deny aid to the speedy (those who advance); others, that it would be cruel to deny it to the needy (those who stagnate). Aid is thus like champagne: in success you deserve it, in failure you need it.”

IV. The Debt Trap

“The concept of the Third World or the South and the policy of official aid are inseparable. They are two sides of the same coin. The Third World is the creation of the foreign aid: without foreign aid there is no Third World.”

According to the World Bank, its objective is “to help raise living standards in developing countries by channeling financial resources from developed countries to the developing world.”

But what if the reality is the opposite?

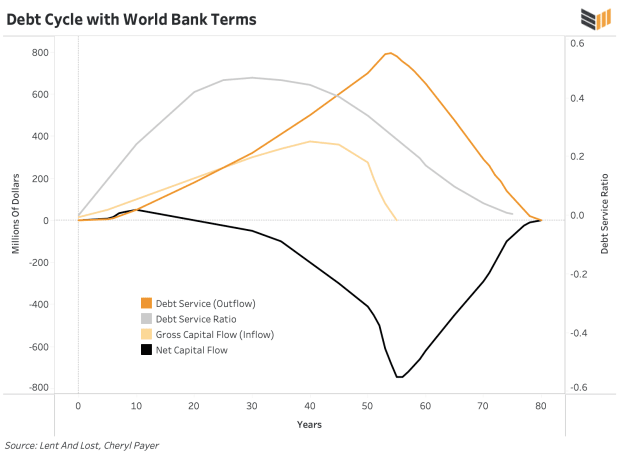

At first, beginning in the 1960s, there was an enormous flow of resources from rich countries to poor ones. This was ostensibly done to help them develop. Payer writes that it was long considered “natural” for capital to “flow in one direction only from the developed industrial economies to the Third World.”

But, as she reminds us, “at some point the borrower has to pay more to his creditor than he has received from the creditor and over the life of the loan this excess is much higher than the amount that was originally borrowed.”

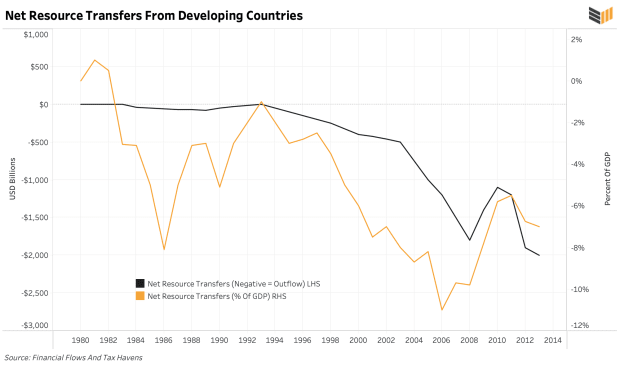

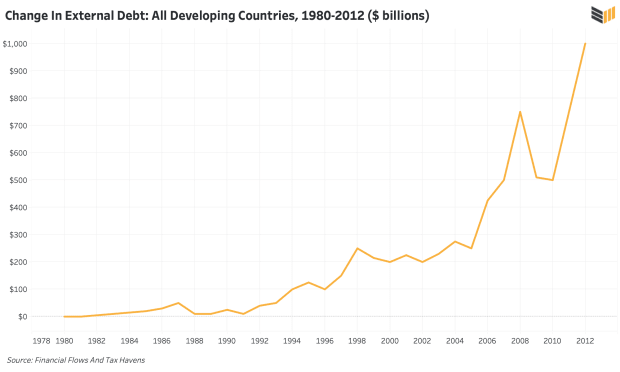

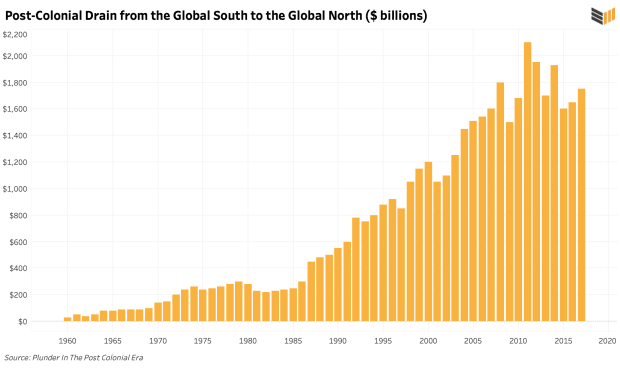

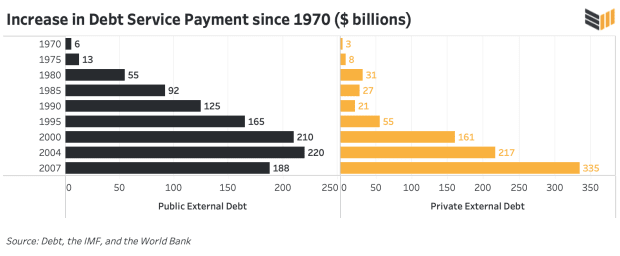

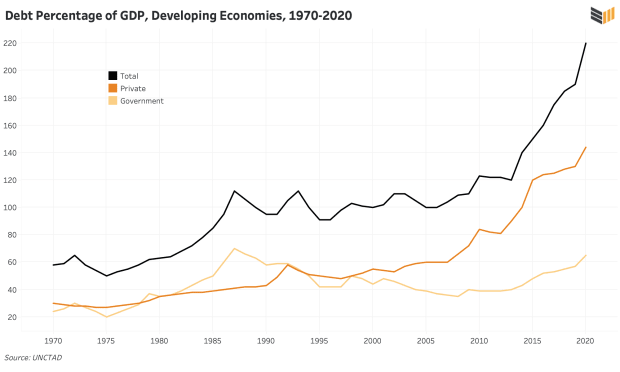

In global economics, this point happened in 1982, when the flow of resources permanently reversed. Ever since, there has been an annual net flow of funds from poor countries to rich ones. This began as an average of $30 billion per year flowing from South to North in the mid-to-late 1980s, and is today in the range of trillions of dollars per year. Between 1970 and 2007 — from the end of the gold standard to the Great Financial Crisis — the total debt service paid by poor countries to rich ones was $7.15 trillion.

To give an example of what this might look like in a given year, in 2012 developing countries received $1.3 trillion, including all income, aid and investment. But that same year, more than $3.3 trillion flowed out. In other words, according to anthropologist Jason Hickel, “developing countries sent $2 trillion more to the rest of the world than they received.”

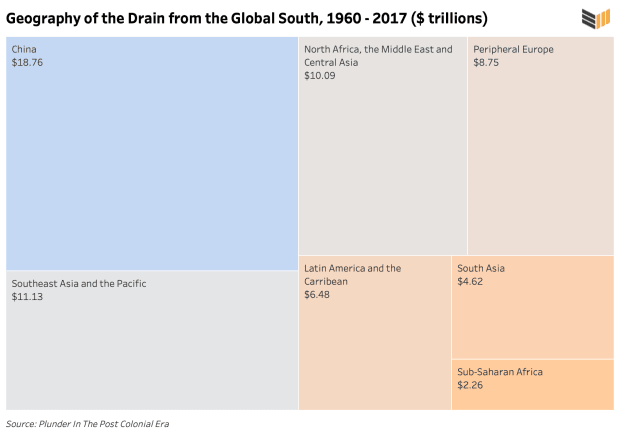

When all the flows were added up from 1960 to 2017, a grim truth emerged: $62 trillion was drained out of the developing world, the equivalent of 620 Marshall Plans in today’s dollars.

The IMF and World Bank were supposed to fix balance of payments issues, and help poor countries grow stronger and more sustainable. The evidence has been the direct opposite.

“For every $1 of aid that developing countries receive,” Hickel writes, “they lose $24 in net outflows.” Instead of ending exploitation and unequal exchange, studies show that structural adjustment policies grew them in a massive way.

Since 1970, the external public debt of developing countries has increased from $46 billion to $8.7 trillion. In the past 50 years, countries like India and the Philippines and the Congo now owe their former colonial masters 189 times the amount they owed in 1970. They have paid $4.2 trillion on interest payments alone since 1980.

Even Payer — whose 1974 book “The Debt Trap” used economic flow data to show how the IMF ensnared poor countries by encouraging them to borrow more than they could possibly pay back — would be shocked at the size of today’s debt trap.

Her observation that “the average citizen of the US or Europe may not be aware of this enormous drain in capital from parts of the world they think of as being pitifully poor” still rings true today. To this author’s own shame, he did not know about the true nature of the global flow of funds and simply assumed that rich countries subsidized poor ones before embarking on the research for this project. The end result is a literal Ponzi scheme, where by the 1970s, Third World debt was so big that it was only possible to service with new debt. It has been the same ever since.

Many critics of the Bank and Fund assume that these institutions are working with their heart in the right place, and when they do fail, it is because of mistakes, waste or mismanagement.

It is the thesis of this essay that this is not true, and that the foundational goals of the Fund and Bank are not to fix poverty but rather to enrich creditor nations at the expense of poor ones.

This author is simply not willing to believe that a permanent flow of funds from poor countries to rich ones since 1982 is a “mistake.” The reader may dispute that the arrangement is intentional, and rather may believe it is an unconscious structural outcome. The difference hardly matters to the billions of people the Bank and Fund have impoverished.

V. Replacing the Colonial Resource Drain

“I am so tired of waiting. Aren’t you, for the world to become good and beautiful and kind? Let us take a knife and cut the world in two — and see what worms are eating at the rind.”

By the end of the 1950s, Europe and Japan had largely recovered from war and resumed significant industrial growth, while Third World countries ran out of funds. Despite having healthy balance sheets in the 1940s and early 1950s, poor, raw-material-exporting countries ran into balance-of-payments issues as the value of their commodities tanked in the wake of the Korean War. This is when the debt trap began, and when the Bank and Fund started the floodgates of what would end up becoming trillions of dollars of lending.

This era also marked the official end of colonialism, as European empires drew back from their imperial possessions. The establishment assumption in international development is that the economic success of nations is due “primarily to their internal, domestic conditions. High-income countries have achieved economic success,” the theory goes, “because of good governance, strong institutions and free markets. Lower-income countries have failed to develop because they lack these things, or because they suffer from corruption, red tape and inefficiency.”

This is certainly true. But another major reason why rich countries are rich and poor countries are poor is that the former looted the latter for hundreds of years during the colonial period.

“Britain’s industrial revolution,” Jason Hickel writes, “depended in large part on cotton, which was grown on land forcibly appropriated from Indigenous Americans, with labor appropriated from enslaved Africans. Other crucial inputs required by British manufacturers — hemp, timber, iron, grain — were produced using forced labor on serf estates in Russia and Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, British extraction from India and other colonies funded more than half the country’s domestic budget, paying for roads, public buildings, the welfare state — all the markets of modern development — while enabling the purchase of material inputs necessary for industrialization.”

The theft dynamic was described by Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik in their book “Capital And Imperialism”: colonial powers like the British empire would use violence to extract raw materials from weak countries, creating a “colonial drain” of capital that boosted and subsidized life in London, Paris and Berlin. Industrial nations would transform these raw materials into manufactured goods, and sell them back to weaker nations, profiting massively while also crowding out local production. And — critically — they would keep inflation at home down by suppressing wages in the colonial territories. Either through outright slavery or through paying well below the global market rate.

As the colonial system began to falter, the Western financial world faced a crisis. The Patnaiks argue that the Great Depression was a result not simply of changes in Western monetary policy, but also of the colonial drain slowing down. The reasoning is simple: rich countries had built a conveyor belt of resources flowing from poor countries, and when the belt broke, so did everything else. Between the 1920s and 1960s, political colonialism became virtually extinct. Britain, the U.S., Germany, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Belgium and other empires were forced to give up control over more than half of the world’s territory and resources.

As the Patnaiks write, imperialism is “an arrangement for imposing income deflation on the Third World population in order to get their primary commodities without running into the problem of increasing supply price.”

Post 1960, this became the new function for the World Bank and IMF: recreating the colonial drain from poor countries to rich countries that was once maintained by straightforward imperialism.

Officials in the U.S., Europe and Japan wanted to achieve “internal equilibrium” — in other words, full employment. But they realized they could not do this via subsidy inside an isolated system, or else inflation would run rampant. To achieve their goal would require external input from poorer countries. The extra surplus value extracted by the core from workers in the periphery is known as “imperialist rent.” If industrial countries could get cheaper materials and labor, and then sell the finished goods back at a profit, they could inch closer to the technocrat dream economy. And they got their wish: as of 2019, wages paid to workers in the developing world were 20% the level of wages paid to workers in the developed world.

As an example of how the Bank recreated the colonial drain dynamic, Payer gives the classic case of 1960s Mauritania in northwest Africa. A mining project called MIFERMA was signed by French occupiers before the colony became independent. The deal eventually became “just an old-fashioned enclave project: a city in a desert and a railroad leading to the ocean,” as the infrastructure was solely focused on spiriting minerals away to international markets. In 1969, when the mine accounted for 30% of Mauritania’s GDP and 75% of its exports, 72% of the income was sent abroad, and “practically all the income distributed locally to employees evaporated in imports.” When the miners protested against the neocolonial arrangement, security forces savagely put them down.

MIFERMA is a stereotypical example of the kind of “development” that would be imposed on the Third World everywhere from the Dominican Republic to Madagascar to Cambodia. And of these projects rapidly expanded in the 1970s, thanks to the petrodollar system.

Post-1973, Arab OPEC countries with enormous surpluses from skyrocketing oil prices sank their profits into deposits and treasuries in Western banks, which needed a place to lend out their growing resources. Military dictators across Latin America, Africa and Asia made great targets: they had high time preferences and were happy to borrow against future generations.

Helping expedite loan growth was the “IMF put”: private banks started to believe (correctly) that the IMF would bail out countries if they defaulted, protecting their investments. Moreover, interest rates in the mid-1970s were often in negative real territory, further encouraging borrowers. This — combined with World Bank president Robert McNamara’s insistence that assistance expand dramatically — resulted in a debt frenzy. U.S. banks, for example, increased their Third World loan portfolio by 300% to $450 billion between 1978 and 1982.

The problem was that these loans were in large part floating interest rate agreements, and a few years later, those rates exploded as the U.S. Federal Reserve raised the global cost of capital close to 20%. The growing debt burden combined with the 1979 oil price shock and the ensuing global collapse in the price of commodities that power the value of developing country exports paved the way for the Third World Debt Crisis. To make matters worse, very little of the money borrowed by governments during the debt frenzy was actually invested in the average citizen.

In their aptly named book “Debt Squads,” investigative journalists Sue Branford and Bernardo Kucinski explain that between 1976 and 1981, Latin governments (of which 18 of 21 were dictatorships) borrowed $272.9 billion. Out of that, 91.6% was spent on debt servicing, capital flight and building up regime reserves. Only 8.4% was used on domestic investment, and even out of that, much was wasted.

Brazilian civil society advocate Carlos Ayuda vividly described the effect of the petrodollar-fueled drain on his own country:

“The military dictatorship used the loans to invest in huge infrastructure projects — particularly energy projects… the idea behind creating an enormous hydroelectric dam and plant in the middle of the Amazon, for example, was to produce aluminum for export to the North… the government took out huge loans and invested billions of dollars in building the Tucuruí dam in the late 1970s, destroying native forests and removing massive numbers of native peoples and poor rural people that had lived there for generations. The government would have razed the forests, but the deadlines were so short they used Agent Orange to defoliate the region and then submerged the leafless tree trunks underwater… the hydroelectric plant’s energy [was then] sold at $13-20 per megawatt when the actual price of production was $48. So the taxpayers provided subsidies, financing cheap energy for transnational corporations to sell our aluminum in the international market.”

In other words, the Brazilian people paid foreign creditors for the service of destroying their environment, displacing the masses and selling their resources.

Today the drain from low- and middle-income countries is staggering. In 2015, it totaled 10.1 billion tons of raw materials and 182 million person-years of labor: 50% of all goods and 28% of all labor used that year by high-income countries.

VI. A Dance With Dictators

“He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

Of course, it takes two sides to finalize a loan from the Bank or Fund. The problem is that the borrower is typically an unelected or unaccountable leader, who makes the decision without consulting with and without a popular mandate from their citizens.

As Payer writes in “The Debt Trap,” “IMF programs are politically unpopular, for the very good concrete reasons that they hurt local business and depress the real income of the electorate. A government which attempts to carry out the conditions in its Letter of Intent to the IMF is likely to find itself voted out of office.”

Hence, the IMF prefers to work with undemocratic clients who can more easily dismiss troublesome judges and put down street protests. According to Payer, the military coups in Brazil in 1964, Turkey in 1960, Indonesia in 1966, Argentina in 1966 and the Philippines in 1972 were examples of IMF-opposed leaders being forcibly replaced by IMF-friendly ones. Even if the Fund wasn’t directly involved in the coup, in each of these cases, it arrived enthusiastically a few days, weeks or months later to help the new regime implement structural adjustment.

The Bank and Fund share a willingness to support abusive governments. Perhaps surprisingly, it was the Bank that started the tradition. According to development researcher Kevin Danaher, “the Bank’s sad record of supporting military regimes and governments that openly violated human rights began on August 7, 1947, with a $195 million reconstruction loan to the Netherlands. Seventeen days before the Bank approved the loan, the Netherlands had unleashed a war against anti-colonialist nationalist in its huge overseas empire in the East Indies, which had already declared its independence as the Republic of Indonesia.”

“The Dutch,” Danaher writes, “sent 145,000 troops (from a nation with only 10 million inhabitants at the time, economically struggling at 90% of 1939 production) and launched a total economic blockade of nationalist-held areas, causing considerable hunger and health problems among Indonesia’s 70 million inhabitants.”

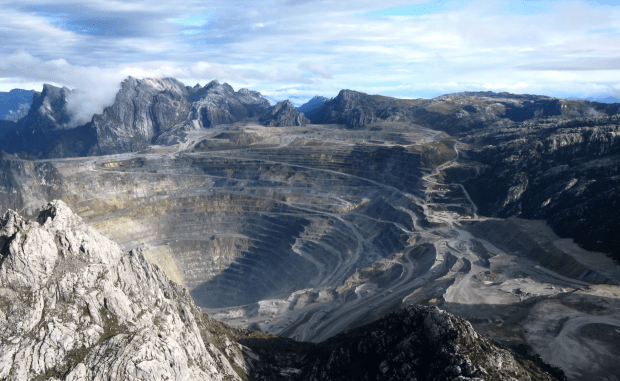

In its first few decades the Bank funded many such colonial schemes, including $28 million for apartheid Rhodesia in 1952, as well as loans to Australia, the United Kingdom, and Belgium to “develop” colonial possessions in Papua New Guinea, Kenya and the Belgian Congo.

In 1966, the Bank directly defied the United Nations, “continuing to lend money to South Africa and Portugal despite resolutions of the General Assembly calling on all UN-affiliated agencies to cease financial support for both countries,” according to Danaher.

Danaher writes that “Portugal’s colonial domination of Angola and Mozambique and South Africa’s apartheid were flagrant violations of the UN charter. But the Bank argued that Article IV, Section 10 of its Charter which prohibits interference in the political affairs of any member, legally obliged it to disregard the UN resolutions. As a result the Bank approved loans of $10 million to Portugal and $20 million to South Africa after the UN resolution was passed.”

Sometimes, the Bank’s preference for tyranny was stark: it cut off lending to the democratically-elected Allende government in Chile in the early 1970s, but shortly after began to lend huge quantities of cash to Ceausescu’s Romania, one of the world’s worst police states. This is also an example of how the Bank and Fund, contrary to popular belief, didn’t simply lend along Cold War ideological lines: for every right-wing Augusto Pinochet Ugarte or Jorge Rafael Videla client, there was a left-wing Josip Broz Tito or Julius Nyerere.

In 1979, Danaher notes, 15 of the world’s most repressive governments would receive a full third of all Bank loans. This even after the U.S. Congress and the Carter administration had stopped aid to four of the 15 — Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Ethiopia — for “flagrant human rights violations.” Just a few years later, in El Salvador, the IMF made a $43 million loan to the military dictatorship, just a few months after its forces committed the largest massacre in Cold War-era Latin America by annihilating the village of El Mozote.

There were several books written about the Bank and the Fund in 1994, timed as 50-year retrospectives on the Bretton Woods institutions. “Perpetuating Poverty” by Ian Vàsquez and Doug Bandow is one of those studies, and is a particularly valuable one as it provides a Libertarian analysis. Most critical studies of the Bank and Fund are from the left: but the Cato Institute’s Vásquez and Bandow saw many of the same problems.

“The Fund underwrites any government,” they write, “however venal and brutal… China owed the Fund $600 million as of the end of 1989; in January 1990, just a few months after the blood had dried in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, the IMF held a seminar on monetary policy in the city.”

Vásquez and Bandow mention other tyrannical clients ranging from military Burma, to Pinochet’s Chile, Laos, Nicaragua under Anastasio Somoza Debayle and the Sandinistas, Syria, and Vietnam.

“The IMF,” they say, “has rarely met a dictatorship that it did not like.”

Vásquez and Bandow detail the Bank’s relationship with the Marxist-Leninist Mengistu Haile Mariam regime in Ethiopia, where it provided for as much as 16% of the government’s annual budget while it had one of the worst human rights records in the world. The Bank’s credit arrived just as Mengistu’s forces were “herding people into concentration camps and collective farms.” They also point out how the Bank gave the Sudanese regime $16 million while it was driving 750,000 refugees out of Khartoum into the desert, and how it gave hundreds of millions of dollars to Iran — a brutal theocratic dictatorship — and Mozambique, whose security forces were infamous for torture, rape and summary executions.

In his 2011 book “Defeating Dictators,” the celebrated Ghanaian development economist George Ayittey detailed a long list of “aid-receiving autocrats”: Paul Biya, Idriss Déby, Lansana Conté, Paul Kagame, Yoweri Museveni, Hun Sen, Islam Karimov, Nursultan Nazarbayev and Emomali Rahmon. He pointed out that the Fund had dispensed $75 billion to these nine tyrants alone.

In 2014, a report was released by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, alleging that the Ethiopian government had used part of a $2 billion Bank loan to forcibly relocate 37,883 indigenous Anuak families. This was 60% of the country’s entire Gambella province. Soldiers “beat, raped, and killed” Anuak who refused to leave their homes. Atrocities were so bad that South Sudan granted refugee status to Anuaks streaming in from neighboring Ethiopia. A Human Rights Watch report said that the stolen land was then “leased by the government to investors” and that the Bank’s money was “used to pay the salaries of government officials who helped carry out the evictions.” The Bank approved new funding for this “villagization” program even after allegations of mass human rights violations emerged.

It would be a mistake to leave Mobutu Sese Soko’s Zaire out of this essay. The recipient of billions of dollars of Bank and Fund credit during his bloody 32-year reign, Mobutu pocketed 30% of incoming aid and assistance and let his people starve. He complied with 11 IMF structural adjustments: during one in 1984, 46,000 public school teachers were fired and the national currency was devalued by 80%. Mobutu called this austerity “a bitter pill which we have no alternative but to swallow,” but didn’t sell any of his 51 Mercedes, any of his 11 chateaus in Belgium or France, or even his Boeing 747 or 16th century Spanish castle.

Per capita income declined in each year of his rule on average by 2.2%, leaving more than 80% of the population in absolute poverty. Children routinely died before the age of five, and swollen-belly syndrome was rampant. It is estimated that Mobutu personally stole $5 billion, and presided over another $12 billion in capital flight, which together would have been more than enough to wipe the country’s $14 billion debt clean at the time of his ouster. He looted and terrorized his people, and could not have done it without the Bank and Fund, which continued to bail him out even though it was clear he would never repay his debts.

That all said, the true poster boy for the Bank and Fund’s affection for dictators might be Ferdinand Marcos. In 1966, when Marcos came to power, the Philippines was the second-most prosperous country in Asia, and the country’s foreign debt stood at roughly $500 million. By the time Marcos was removed in 1986, the debt stood at $28.1 billion.

As Graham Hancock writes in “Lords Of Poverty,” most of these loans “had been contracted to pay for extravagant development schemes which, although irrelevant to the poor, had pandered to the enormous ego of the head of state… a painstaking two-year investigation established beyond serious dispute that he had personally expropriated and sent out of the Philippines more than $10 billion. Much of this money — which of course, should have been at the disposal of the Philippine state and people — had disappeared forever in Swiss bank accounts.”

“$100 million,” Hancock writes, “was paid for the art collection for Imelda Marcos… her tastes were eclectic and included six Old Masters purchased from the Knodeler Gallery in New York for $5 million, a Francis Bacon canvas supplied by the Marlborough Gallery in London, and a Michelangelo, ‘Madonna and Child’ bought from Mario Bellini in Florence for $3.5 million.”

“During the last decade of the Marcos regime,” he says, “while valuable art treasuries were being hung on penthouse walls in Manhattan and Paris, the Philippines had lower nutritional standards than any other nation in Asia with the exception of war-torn Cambodia.”

To contain popular unrest, Hancock writes that Marcos banned strikes and “union organizing was outlawed in all key industries and in agriculture. Thousands of Filipinos were imprisoned for opposing the dictatorship and many were tortured and killed. Meanwhile the country remained consistently listed among the top recipients of both US and World Bank development assistance.”

After the Filipino people pushed Marcos out, they still had to pay an annual sum of anywhere between 40% and 50% of the entire value of their exports “just to cover the interest on the foreign debts that Marcos incurred.”

One would think that after ousting Marcos, the Filipino people would not have to owe the debt he incurred on their behalf without consulting them. But that is not how it has worked in practice. In theory, this concept is called “odious debt” and was invented by the U.S. in 1898 when it repudiated Cuba’s debt after Spanish forces were ousted from the island.

American leaders determined that debts “incurred to subjugate a people or to colonize them” were not legitimate. But the Bank and Fund have never followed this precedent during their 75 years of operations. Ironically, the IMF has an article on its website suggesting that Somoza, Marcos, Apartheid South Africa, Haiti’s “Baby Doc” and Nigeria’s Sani Abacha all borrowed billions illegitimately, and that the debt should be written off for their victims, but this remains a suggestion unfollowed.

Technically and morally speaking, a large percentage of Third World debt should be considered “odious” and not owed anymore by the population should their dictator be forced out. After all, in most cases, the citizens paying back the loans didn’t elect their leader and didn’t choose to borrow the loans that they took out against their future.

In July 1987, the revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara gave a speech to the Organistion of African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia, where he refused to pay the colonial debt of Burkina Faso, and encouraged other African nations to join him.

“We cannot pay,” he said, “because we are not responsible for this debt.”

Sankara famously boycotted the IMF and refused structural adjustment. Three months after his OAU speech, he was assassinated by Blaise Compaoré, who would install his own 27-year military regime that would receive four structural adjustment loans from the IMF and borrow dozens of times from the World Bank for various infrastructure and agriculture projects. Since Sankara’s death, few heads of state have been willing to take a stand to repudiate their debts.

One big exception was Iraq: after the U.S. invasion and ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003, American authorities managed to get some of the debt incurred by Hussein to be considered “odious” and forgiven. But this was a unique case: for the billions of people who suffered under colonialists or dictators, and have since been forced to pay their debts plus interest, they have not gotten this special treatment.

In recent years, the IMF has even acted as a counter-revolutionary force against democratic movements. In the 1990s, the Fund was widely criticized on the left and the right for helping to destabilize the former Soviet Union as it descended into economic chaos and congealed into Vladimir Putin’s dictatorship. In 2011, as the Arab Spring protests emerged across the Middle East, the Deauville Partnership with Arab Countries in Transition was formed and met in Paris.

Through this mechanism, the Bank and Fund led massive loan offers to Yemen, Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco and Jordan — “Arab countries in transition” — in exchange for structural adjustment. As a result, Tunisia’s foreign debt skyrocketed, triggering two new IMF loans, marking the first time that the country had borrowed from the Fund since 1988. The austerity measures paired with these loans forced the devaluation of the Tunisian dinar, which spiked prices. National protests broke out as the government continued to follow the Fund playbook with wage freezes, new taxes and “early retirement” in the public sector.

Twenty-nine-year-old protestor Warda Atig summed up the situation: “As long as Tunisia continues these deals with the IMF, we will continue our struggle,” she said. “We believe that the IMF and the interests of people are contradictory. An escape from submission to the IMF, which has brought Tunisia to its knees and strangled the economy, is a prerequisite to bring about any real change.”

VII. Creating Agricultural Dependence

“The idea that developing countries should feed themselves is an anachronism from a bygone era. They could better ensure their food security by relying on the U.S. agricultural products, which are available in most cases at lower cost.”

–Former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture John Block

As a result of Bank and Fund policy, all across Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and South and East Asia, countries which once grew their own food now import it from rich countries. Growing one’s own food is important, in retrospect, because in the post-1944 financial system, commodities are not priced with one’s local fiat currency: they are priced in the dollar.

Consider the price of wheat, which ranged between $200 and $300 between 1996 and 2006. It has since skyrocketed, peaking at nearly $1,100 in 2021. If your country grew its own wheat, it could weather the storm. If your country had to import wheat, your population risked starvation. This is one reason why countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Ghana and Bangladesh are all currently turning to the IMF for emergency loans.

Historically, where the Bank did give loans, they were mostly for “modern,” large-scale, mono-crop agriculture and for resource extraction: not for the development of local industry, manufacturing or consumption farming. Borrowers were encouraged to focus on raw materials exports (oil, minerals, coffee, cocoa, palm oil, tea, rubber, cotton, etc.), and then pushed to import finished goods, foodstuffs and the ingredients for modern agriculture like fertilizer, pesticides, tractors and irrigation machinery. The result is that societies like Morocco end up importing wheat and soybean oil instead of thriving on native couscous and olive oil, “fixed” to become dependent. Earnings were typically used not to benefit farmers, but to service foreign debt, purchase weapons, import luxury goods, fill Swiss bank accounts and put down dissent.

Consider some of the world’s poorest countries. As of 2020, after 50 years of Bank and Fund policy, Niger’s exports were 75% uranium; Mali’s 72% gold; Zambia’s 70% copper; Burundi’s 69% coffee; Malawi’s 55% tobacco; Togo’s 50% cotton; and on it goes. At times in past decades, these single exports supported virtually all of these countries’ hard currency earnings. This is not a natural state of affairs. These items are not mined or produced for local consumption, but for French nuclear plants, Chinese electronics, German supermarkets, British cigarette makers, and American clothing companies. In other words, the energy of the labor force of these nations has been engineered toward feeding and powering other civilizations, instead of nourishing and advancing their own.

Researcher Alicia Koren wrote about the typical agricultural impact of Bank policy in Costa Rica, where the country’s “structural adjustment called for earning more hard currency to pay off foreign debt; forcing farmers who traditionally grew beans, rice, and corn for domestic consumption to plant non-traditional agricultural exports such as ornamental plants, flowers, melons, strawberries, and red peppers… industries that exported their products were eligible for tariff and tax exemptions not available to domestic producers.”

“Meanwhile,” Koren wrote, “structural adjustment agreements removed support for domestic production… while the North pressured Southern nations to eliminate subsidies and ‘barriers to trade,’ Northern governments pumped billions of dollars into their own agricultural sectors, making it impossible for basic grains growers in the South to compete with the North’s highly subsidized agricultural industry.”

Koren extrapolated her Costa Rica analysis to make a broader point: “Structural adjustment agreements shift public spending subsidies from basic supplies, consumed mainly by the poor and middle classes, to luxury export crops produced for affluent foreigners.” Third World countries were not seen as body politics but as companies that needed to increase revenues and decrease expenditures.

The testimony of a former Jamaican official is especially telling: “We told the World Bank team that farmers could hardly afford credit, and that higher rates would put them out of business. The Bank told us in response that this means ‘The market is telling you that agriculture is not the way to go for Jamaica’ — they are saying we should give up farming altogether.”

“The World Bank and IMF,” the official said, “don’t have to worry about the farmers and local companies going out of business, or starvation wages or the social upheaval that will result. They simply assume that it is our job to keep our national security forces strong enough to suppress any uprising.”

Developing governments are stuck: faced with insurmountable debt, the only factor they really control in terms of increasing revenue is deflating wages. If they do this, they must provide basic food subsidies, or else they will be overthrown. And so the debt grows.

Even when developing countries try to produce their own food, they are crowded out by a centrally-planned global trade market. For example, one would think that the cheap labor in a place like West Africa would make it a better exporter of peanuts than the United States. But since Northern countries pay an estimated $1 billion in subsidies to their agriculture industries every single day, Southern countries often struggle to be competitive. What’s worse, 50 or 60 countries are often directed to focus on the very same crops, crowding each other out in the global marketplace. Rubber, palm oil, coffee, tea and cotton are Bank favorites, as the poor masses can’t eat them.

It is true that the Green Revolution has created more food for the planet, especially in China and East Asia. But despite advances in agricultural technology, much of these new yields go to exports, and vast swathes of the world remain chronically malnourished and dependent. To this day, for example, African nations import about 85% of their food. They pay more than $40 billion per year — a number estimated to reach $110 billion per year by 2025 — to buy from other parts of the world what they could grow themselves. Bank and Fund policy helped transform a continent of incredible agricultural riches into one reliant on the outside world to feed its people.

Reflecting on the results of this policy of dependency, Hancock challenges the widespread belief that the people of the Third World are “fundamentally helpless.”

“Victims of nameless crises, disasters, and catastrophes,” he writes, suffer from a perception that “they can do nothing unless we, the rich and powerful, intervene to save them from themselves.” But as evidenced by the fact that our “assistance” has only made them more dependent on us, Hancock rightfully unmasks the notion that “only we can save them” as “patronizing and profoundly fallacious.”

Far from playing the role of good samaritan, the Fund does not even follow the timeless human tradition, established more than 4,000 years ago by Hammurabi in ancient Babylon, of forgiving interest after natural disasters. In 1985, a devastating earthquake hit Mexico City, killing more than 5,000 people and causing $5 billion of damage. Fund staff — who claim to be saviors, helping to end poverty and save countries in crisis — arrived a few days later, demanding to be repaid.

VIII. You Can’t Eat Cotton

“Development prefers crops that can’t be eaten so the loans can be collected.”

The Togolese democracy advocate Farida Nabourema’s own personal and family experience tragically matches the big picture of the Bank and Fund laid out thus far.

The way she puts it, after the 1970s oil boom, loans were poured into developing nations like Togo, whose unaccountable rulers didn’t think twice about how they would repay the debt. Much of the money went into giant infrastructure projects that didn’t help the majority of the people. Much was embezzled and spent on pharaonic estates. Most of these countries, she says, were ruled by single party-states or families. Once interest rates started to hike, these governments could no longer pay their debts: the IMF started “taking over” by imposing austerity measures.

“These were new states that were very fragile,” Nabourema says in an interview for this article. “They needed to invest strongly in social infrastructure, just as the European states were allowed to do after World War II. But instead, we went from free healthcare and education one day, to situations the next where it became too costly for the average person to get even basic medicine.”

Regardless of what one thinks about state-subsidized medicine and schooling, eliminating it overnight was traumatic for poor countries. Bank and Fund officials, of course, have their own private healthcare solutions for their visits and their own private schools for their children whenever they have to live “in the field.”

Because of the forced cuts in public spending, Nabourema says, the state hospitals in Togo remain to this day in “complete decay.” Unlike the state-run, taxpayer-financed public hospitals in the capitals of former colonial powers in London and Paris, things are so bad in Togo’s capital Lomé that even water has to be prescribed.

“There was also,” Nabourema said, “reckless privatization of our public companies.” She explained how her father used to work at the Togolese steel agency. During privatization, the company was sold off to foreign actors for less than half of what the state built it for.

“It was basically a garage sale,” she said.

Nabourema says that a free market system and liberal reforms work well when all participants are on an equal playing field. But that is not the case in Togo, which is forced to play by different rules. No matter how much it opens up, it can’t change the strict policies of the U.S. and Europe, who aggressively subsidize their own industries and agriculture. Nabourema mentions how a subsidized influx of cheap used clothes from America, for example, ruined Togo’s local textile industry.

“These clothes from the West,” she said, “put entrepreneurs out of business and littered our beaches.”

The most horrible aspect, she said, is that the farmers — who made up 60% of the population in Togo in the 1980s — had their livelihoods turned upside down. The dictatorship needed hard currency to pay its debts, and could only do this by selling exports, so they began a massive campaign to sell cash crops. With the World Bank’s help, the regime invested heavily in cotton, so much so that it now dominates 50% of the country’s exports, destroying national food security.

In the formative years for countries like Togo, the Bank was the “largest single lender for agriculture.” Its strategy for fighting poverty was agricultural modernization: “massive transfers of capital, in the form of fertilizers, pesticides, earth-moving equipment, and expensive foreign consultants.”

Nabourema’s father was the one who revealed to her how imported fertilizers and tractors were diverted away from farmers growing consumption food, to farmers growing cash crops like cotton, coffee, cocoa and cashews. If someone was growing corn, sorghum or millet — the basic foodstuffs of the population — they didn’t get access.

“You can’t eat cotton,” Nabourema reminds us.

Over time, the political elite in countries like Togo and Benin (where the dictator was literally a cotton mogul) became the buyer of all the cash crops from all of the farms. They’d have a monopoly on purchases, Nabourema says, and would buy the crops for prices so low that the peasants would barely make any money. This entire system — called “sotoco” in Togo — was based on funding provided by the World Bank.

When farmers would protest, she said, they would get beaten or their farms would get burned to rubble. They could have just grown normal food and fed their families, like they had done for generations. But now they could not even afford the land: the political elite has been acquiring land at an outrageous rate, often through illegal means, jacking up the price.

As an example, Nabourema explains how the Togolese regime might seize 2,000 acres of land: unlike in a liberal democracy (like the one in France, which has built its civilization off the backs of countries like Togo), the judicial system is owned by the government, so there is no way to push back. So farmers, who used to be self-sovereign, are now forced to work as laborers on someone else’s land to provide cotton to rich countries far away. The most tragic irony, Nabourema says, is that cotton is overwhelmingly grown in the north of Togo, in the poorest part of the country.

“But when you go there,” she says, “you see it has made no one rich.”

Women bear the brunt of structural adjustment. The misogyny of the policy is “quite clear in Africa, where women are the major farmers and providers of fuel, wood, and water,” Danaher writes. And yet, a recent retrospective says, “the World Bank prefers to blame them for having too many children rather than reexamining its own policies.”

As Payer writes, for many of the world’s poor, they are poor “not because they have been left behind or ignored by their country’s progress, but because they are the victims of modernisation. Most have been crowded off the good farmland, or deprived of land altogether, by rich elites and local or foreign agribusiness. Their destitution has not ‘ruled them out’ of the development process; the development process has been the cause of their destitution.”

“Yet the Bank,” Payer says, “is still determined to transform the agricultural practices of small farmers. Bank policy statements make it clear that the real aim is integration of peasant land into the commercial sector through the production of a ‘marketable surplus’ of cash crops.”

Payer observed how, in the 1970s and 1980s, many small plotters still grew the bulk of their own food needs, and were not “dependent on the market for the near-totality of their sustenance, as ‘modern’ people were.” These people, however, were the target of the Bank’s policies, which transformed them into surplus producers, and “often enforced this transformation with authoritarian methods.”

In a testimony in front of U.S. Congress in the 1990s, George Ayittey remarked that “if Africa were able to feed itself, it could save nearly $15 billion it wastes on food imports. This figure may be compared with the $17 billion Africa received in foreign aid from all sources in 1997.”

In other words, if Africa grew its own food, it wouldn’t need foreign aid. But if that were to happen, then poor countries wouldn’t be buying billions of dollars of food per year from rich countries, whose economies would shrink as a result. So the West strongly resists any change.

IX. The Development Set

Excuse me, friends, I must catch my jet

I'm off to join the Development Set

My bags are packed, and I've had all my shots

I have traveller's checks and pills for the trots!

The Development Set is bright and noble

Our thoughts are deep and our vision global

Although we move with the better classes

Our thoughts are always with the masses

In Sheraton Hotels in scattered nations

We damn multinational corporations

Injustice seems easy to protest

In such seething hotbeds of social rest.

We discuss malnutrition over steaks

And plan hunger talks during coffee breaks.

Whether Asian floods or African drought

We face each issue with open mouth.

And so begins “The Development Set,” a 1976 poem by Ross Coggins that hits at the heart of the paternalistic and unaccountable nature of the Bank and the Fund.

The World Bank pays high, tax-free salaries, with very generous benefits. IMF staff are paid even better, and traditionally were flown first or business class (depending on the distance), never economy. They stayed in five-star hotels, and even had a perk to get free upgrades onto the supersonic Concorde. Their salaries, unlike wages made by people living under structural adjustment, were not capped and always rose faster than the inflation rate.

Until the mid-1990s the janitors cleaning the World Bank headquarters in Washington — mostly immigrants who fled from countries that the Bank and Fund had “adjusted” — were not even allowed to unionize. In contrast, Christine Lagarde’s tax-free salary as head of the IMF was $467,940, plus an additional $83,760 allowance. Of course, during her term from 2011 to 2019, she oversaw a variety of structural adjustments on poor countries, where taxes on the most vulnerable were almost always raised.

Graham Hancock notes that redundancy payments at the World Bank in the 1980s “averaged a quarter of a million dollars per person.” When 700 executives lost their jobs in 1987, the money spent on their golden parachutes — $175 million — would have been enough, he notes, “to pay for a complete elementary school education for 63,000 children from poor families in Latin America or Africa.”

According to former World Bank head James Wolfensohn, from 1995 to 2005 there were more than 63,000 Bank projects in developing countries: the costs of “feasibility studies” and travel and lodging for experts from industrialized countries alone absorbed as much as 25% of the total aid.

Fifty years after the creation of the Bank and Fund, “90% of the $12 billion per year in technical assistance was still spent on foreign expertise.” That year, in 1994, George Ayittey noted that 80,000 Bank consultants worked on Africa alone, but that “less than .01%” were Africans.

Hancock writes that “the Bank, which puts more money into more schemes in more developing countries than any other institution, claims that ‘it seeks to meet the needs of the poorest people;’ but at no stage in what it refers to as the ‘project cycle’ does it actually take the time to ask the poor themselves how they perceive their needs… the poor are entirely left out of the decision-making progress — almost as if they don’t exist.”

Bank and Fund policy is forged in meetings in lavish hotels between people who will never have to live a day in poverty in their lives. As Joseph Stiglitz argues in his own criticism of the Bank and Fund, “modern high-tech warfare is designed to remove physical contact: dropping bombs from 50,000 feet ensures that one does not ‘feel’ what one does. Modern economic management is similar: from one’s luxury hotel, one can callously impose policies about which one would think twice if one knew the people whose lives one was destroying.”

Strikingly, Bank and Fund leaders are sometimes the very same people who drop the bombs. For example, Robert McNamara — probably the most transformative person in Bank history, famous for massively expanding its lending and sinking poor countries into inescapable debt — was first the CEO of the Ford corporation, before becoming U.S. defense secretary, where he sent 500,000 American troops to fight in Vietnam. After leaving the Bank, he went straight to the board of Royal Dutch Shell. A more recent World Bank head was Paul Wolfowitz, one of the key architects of the Iraq War.

The development set makes its decisions far away from the populations who end up feeling the impact, and they hide the details behind mountains of paperwork, reports and euphemistic jargon. Like the old British Colonial Office, the set conceals itself “like a cuttlefish, in a cloud of ink.”

The prolific and exhausting histories written by the set are hagiographies: the human experience is airbrushed out. A good example is a study called “Balance of Payments Adjustment, 1945 to 1986: The IMF Experience.” This author had the tedious experience of reading the entire tome. Benefits from colonialism are entirely ignored. The personal stories and human experiences of the people who suffered under Bank and Fund policy are elided. Hardship is buried under countless charts and statistics. These studies, which dominate the discourse, read as if their main priority is to avoid offending Bank or Fund staff. Sure, the tone implies that perhaps mistakes were made here or there, but the intentions of the Bank and Fund are good. They are here to help.

In one example from the aforementioned study, structural adjustment in Argentina in 1959 and 1960 is described as such: “While the measures had initially reduced the standard of living of a vast sector of the Argentine population, in relatively short time these measures had resulted in a favorable trade balance and balance of payments, an increase in foreign exchange reserves, a sharp reduction in the rate of increases in the cost of living, a stable exchange rate, and increased domestic and foreign investment.”

In layman’s terms: Sure, there was enormous impoverishment of the entire population, but hey, we got a better balance sheet, more savings for the regime, and more deals with multinational corporations.

The euphemisms keep coming. Poor countries are consistently described as “test cases.” The lexicon and jargon and language of development economics is designed to hide what is actually happening, to mask the cruel reality with terms and process and theory, and to avoid stating the underlying mechanism: rich countries siphoning resources from poor countries and enjoying double standards that enrich their populations while impoverishing people elsewhere.

The apotheosis of the Bank and Fund’s relationship with the developing world is their annual meeting in Washington, D.C.: a grand festival on poverty in the richest country on earth.

“Over mountainous piles of beautifully prepared food,” Hancock writes, “huge volumes of business get done; meanwhile staggering displays of dominance and ostentation get smoothly blended with empty and meaningless rhetoric about the predicament of the poor.”

“The 10,000 men and women attending,” he writes, “look extraordinarily unlikely to achieve [their] noble objectives; when not yawning or asleep at the plenary sessions they are to be found enjoying a series of cocktail parties, lunches, afternoon teas, dinners, and midnight snacks lavish enough to surfeit the greenest gourmand. The total cost of the 700 social events laid on for delegates during a single week [in 1989] was estimated at $10 million — a sum of money that might, perhaps, have better ‘served the needs of the poor’ had it been spent in some other way.”

This was 33 years ago: one can only imagine the cost of these parties in today’s dollars.

In his book “The Fiat Standard,” Saifedean Ammous has a different name for the development set: the misery industry. His description is worth quoting at length:

“When World Bank planning inevitably fails and the debts cannot be repaid, the IMF comes in to shake down the deadbeat countries, pillage their resources, and take control of political institutions. It is a symbiotic relationship between the two parasitic organizations that generates a lot of work, income and travel for the misery industry’s workers — at the expense of the poor countries that have to pay for it all in loans.”

“The more one reads about it,” Ammous writes, “the more one realizes how catastrophic it has been to hand this class of powerful yet unaccountable bureaucrats an endless line of fiat credit and unleash them on the world’s poor. This arrangement allows unelected foreigners with nothing at stake to control and centrally plan entire nations’ economies…. Indigenous populations are removed from their lands, private businesses are closed to protect monopoly rights, taxes are raised, and property is confiscated… tax-free deals are provided to international corporations under the auspices of the International Financial Institutions, while local producers pay ever-higher taxes and suffer from inflation to accommodate their governments’ fiscal incontinence.”

“As part of the debt relief deals signed with the misery industry,” he continues, “governments were asked to sell off some of their most prized assets. This included government enterprises, but also national resources and entire swaths of land. The IMF would usually auction these to multinational corporations and negotiate with governments for them to be exempt from local taxes and laws. After decades of saturating the world with easy credit, the IFIs spent the 1980s acting as repo men. They went through the wreckage of third-world countries devastated by their policies and sold whatever was valuable to multinational corporations, giving them protection from the law in the scrap heaps in which they operated. This reverse Robin Hood redistribution was the inevitable consequence of the dynamics created when these organizations were endowed with easy money.”

“By ensuring the whole world stays on the U.S. dollar standard,” Ammous concludes, “the IMF guarantees the US can continue to operate its inflationary monetary policy and export its inflation globally. Only when one understands the grand larceny at the heart of the global monetary system can one understand the plight of developing countries.”

X. White Elephants

“What Africa needs to do is grow, grow out of debt.”

–George Ayittey